Working with Sequences

Up until now, we have focused on models whose inputs consisted of a single feature vector

Some datasets consist of a single massive sequence. Consider, for example, the extremely long streams of sensor readings that might be available to climate scientists. In such cases, we might create training datasets by randomly sampling subsequences of some predetermined length. More often, our data arrives as a collection of sequences. Consider the following examples: (i) a collection of documents, each represented as its own sequence of words, and each having its own length

Previously, when dealing with individual inputs, we assumed that they were sampled independently from the same underlying distribution

This should come as no surprise. If we did not believe that the elements in a sequence were related, we would not have bothered to model them as a sequence in the first place. Consider the usefulness of the auto-fill features that are popular on search tools and modern email clients. They are useful precisely because it is often possible to predict (imperfectly, but better than random guessing) what the likely continuations of a sequence might be, given some initial prefix. For most sequence models, we do not require independence, or even stationarity, of our sequences. Instead, we require only that the sequences themselves are sampled from some fixed underlying distribution over entire sequences.

This flexible approach allows for such phenomena as (i) documents looking significantly different at the beginning than at the end; or (ii) patient status evolving either towards recovery or towards death over the course of a hospital stay; or (iii) customer taste evolving in predictable ways over the course of continued interaction with a recommender system.

We sometimes wish to predict a fixed target

Before we worry about handling targets of any kind, we can tackle the most straightforward problem: unsupervised density modeling (also called sequence modeling). Here, given a collection of sequences, our goal is to estimate the probability mass function that tells us how likely we are to see any given sequence, i.e.,

using Pkg; Pkg.activate("../../d2lai")

using d2lai

using Flux

using Plots Activating project at `/workspace/d2l-julia/d2lai`[ Info: Precompiling d2lai [749b8817-cd67-416c-8a57-830ea19f3cc4] (cache misses: include_dependency fsize change (2))

Autoregressive Models

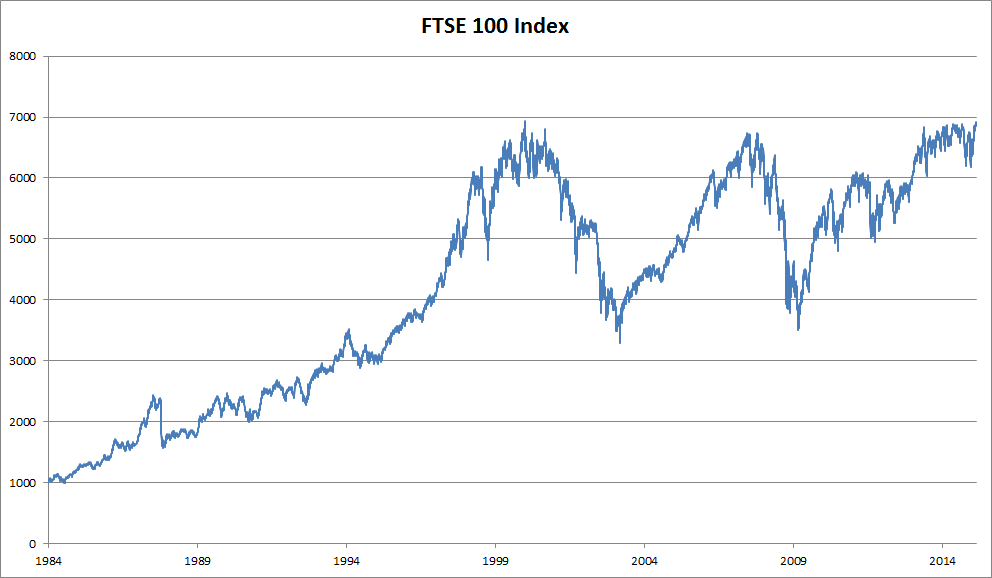

Before introducing specialized neural networks designed to handle sequentially structured data, let's take a look at some actual sequence data and build up some basic intuitions and statistical tools. In particular, we will focus on stock price data from the FTSE 100 index (Figure). At each time step

:width:

:width:400px 🏷️fig_ftse100

Now suppose that a trader would like to make short-term trades, strategically getting into or out of the index, depending on whether they believe that it will rise or decline in the subsequent time step. Absent any other features (news, financial reporting data, etc.), the only available signal for predicting the subsequent value is the history of prices to date. The trader is thus interested in knowing the probability distribution

over prices that the index might take in the subsequent time step. While estimating the entire distribution over a continuously valued random variable can be difficult, the trader would be happy to focus on a few key statistics of the distribution, particularly the expected value and the variance. One simple strategy for estimating the conditional expectation

would be to apply a linear regression model (recall :numref:sec_linear_regression). Such models that regress the value of a signal on the previous values of that same signal are naturally called autoregressive models. There is just one major problem: the number of inputs,

A few strategies recur frequently. First of all, we might believe that although long sequences

A latent autoregressive model.

To construct training data from historical data, one typically creates examples by sampling windows randomly. In general, we do not expect time to stand still. However, we often assume that while the specific values of

Sequence Models

Sometimes, especially when working with language, we wish to estimate the joint probability of an entire sequence. This is a common task when working with sequences composed of discrete tokens, such as words. Generally, these estimated functions are called sequence models and for natural language data, they are called language models. The field of sequence modeling has been driven so much by natural language processing, that we often describe sequence models as "language models", even when dealing with non-language data. Language models prove useful for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes we want to evaluate the likelihood of sentences. For example, we might wish to compare the naturalness of two candidate outputs generated by a machine translation system or by a speech recognition system. But language modeling gives us not only the capacity to evaluate likelihood, but the ability to sample sequences, and even to optimize for the most likely sequences.

While language modeling might not, at first glance, look like an autoregressive problem, we can reduce language modeling to autoregressive prediction by decomposing the joint density of a sequence

Note that if we are working with discrete signals such as words, then the autoregressive model must be a probabilistic classifier, outputting a full probability distribution over the vocabulary for whatever word will come next, given the leftwards context.

Markov Models

Now suppose that we wish to employ the strategy mentioned above, where we condition only on the

We often find it useful to work with models that proceed as though a Markov condition were satisfied, even when we know that this is only approximately true. With real text documents we continue to gain information as we include more and more leftwards context. But these gains diminish rapidly. Thus, sometimes we compromise, obviating computational and statistical difficulties by training models whose validity depends on a

With discrete data, a true Markov model simply counts the number of times that each word has occurred in each context, producing the relative frequency estimate of

The Order of Decoding

You may be wondering why we represented the factorization of a text sequence

However, there are many reasons why factorizing text in the same direction in which we read it (left-to-right for most languages, but right-to-left for Arabic and Hebrew) is preferred for the task of language modeling. First, this is just a more natural direction for us to think about. After all we all read text every day, and this process is guided by our ability to anticipate which words and phrases are likely to come next. Just think of how many times you have completed someone else's sentence. Thus, even if we had no other reason to prefer such in-order decodings, they would be useful if only because we have better intuitions for what should be likely when predicting in this order.

Second, by factorizing in order, we can assign probabilities to arbitrarily long sequences using the same language model. To convert a probability over steps

Third, we have stronger predictive models for predicting adjacent words than words at arbitrary other locations. While all orders of factorization are valid, they do not necessarily all represent equally easy predictive modeling problems. This is true not only for language, but for other kinds of data as well, e.g., when the data is causally structured. For example, we believe that future events cannot influence the past. Hence, if we change

Training

Before we focus our attention on text data, let's first try this out with some continuous-valued synthetic data.

Here, our 1000 synthetic data will follow the trigonometric sin function, applied to 0.01 times the time step. To make the problem a little more interesting, we corrupt each sample with additive noise. From this sequence we extract training examples, each consisting of features and a label.

struct SineData{A} <: d2lai.AbstractData

X::AbstractArray

time::AbstractArray

args::A

end

function SineData(batchsize::Int = 16, T = 1000, num_train = 600, tau = 4)

time = collect(1:1:T)

X = sin.(0.01*time) .+ (randn(T).*0.2)

SineData(X, time, (batchsize = batchsize, num_train = 600, tau = tau, T = T))

end

data = SineData()

plot(data.time, data.X, xlabel = "time", ylabel = "X")To begin, we try a model that acts as if the data satisfied a

function d2lai.get_dataloader(data::SineData; train = true)

features = [data.X[i : data.args.T - data.args.tau + i] for i in 1:data.args.tau]

features = reduce(hcat, features)' |> Matrix

labels = reshape(data.X[data.args.tau:end], 1, :)

if train

return Flux.DataLoader((features[:, 1:data.args.num_train], labels[:, 1:data.args.num_train]), batchsize = data.args.batchsize, shuffle = train)

else

return Flux.DataLoader((features[:, data.args.num_train+1:end], labels[:, data.args.num_train+1:end]), batchsize = data.args.batchsize, shuffle = train)

end

endIn this example our model will be a standard linear regression.

model = LinearRegressionConcise(Dense(4 => 1))

opt = Descent(0.01)

data = SineData()

trainer = Trainer(model, data, opt; max_epochs = 3)

d2lai.fit(trainer) [ Info: Train Loss: 0.15051332964519737, Val Loss: 0.044622991002796604

[ Info: Train Loss: 0.018162010304299737, Val Loss: 0.02343339680249852

[ Info: Train Loss: 0.015179425747226385, Val Loss: 0.02235553277685628(LinearRegressionConcise{Dense{typeof(identity), Matrix{Float32}, Vector{Float32}}}(Dense(4 => 1)), (val_loss = [0.05192562511064459, 0.019020660161435658, 0.02692951634539949, 0.0372197320592554, 0.03865243598795507, 0.021252869015836413, 0.030722447215078854, 0.014665679937061525, 0.0192626657415325, 0.0161218121684424 … 0.030181715305551235, 0.018167196865093393, 0.050209651635706114, 0.016823924857505966, 0.02495666653711767, 0.020662361790426253, 0.04009904816945555, 0.04067374823027833, 0.011067405827883209, 0.02235553277685628], val_acc = nothing))Prediction

To evaluate our model, we first check how well it performs at one-step-ahead prediction

features = [data.X[i : data.args.T - data.args.tau + i] for i in 1:data.args.tau]

features = reduce(hcat, features)' |> Matrix

labels = reshape(data.X[data.args.tau:end], 1, :)

onestep_preds = model.net(features)

plot(data.time[data.args.tau:end], vec(onestep_preds), label = "onestep preds")

plot!(data.time[data.args.tau:end], vec(labels), label = "labels")These predictions look good, even near the end at

But what if we only observed sequence data up until time step 604 (n_train + tau) and wished to make predictions several steps into the future? Unfortunately, we cannot directly compute the one-step-ahead prediction for time step 609, because we do not know the corresponding inputs, having seen only up to

Generally, for an observed sequence

multistep_preds = data.X

for i in (data.args.num_train + data.args.tau) : data.args.T

multistep_preds[i] = model.net(multistep_preds[i - data.args.tau + 1 : i])[1]

end

plot(data.time[data.args.tau:end], vec(onestep_preds), label = "onestep preds")

plot!(data.time[(data.args.num_train + data.args.tau):data.args.T], multistep_preds[(data.args.num_train + data.args.tau):data.args.T])Unfortunately, in this case we fail spectacularly. The predictions decay to a constant pretty quickly after a few steps. Why did the algorithm perform so much worse when predicting further into the future? Ultimately, this is down to the fact that errors build up. Let's say that after step 1 we have some error

Let's take a closer look at the difficulties in

function k_step_pred(k)

features = []

for i in 1:data.args.tau

push!(features, data.X[i : i+data.args.T-data.args.tau-k+1])

end

for i in 1:k

preds = model.net(reduce(hcat, features[i : i+data.args.tau - 1])')

push!(features, vec(preds))

end

return features[data.args.tau:end]

endk_step_pred (generic function with 1 method)steps = (1, 4, 16, 64)

preds = k_step_pred(steps[end])

plot(data.time[data.args.tau+steps[end]-1:end],

reduce(hcat,[preds[k] for k in steps]), xlabel = "time", ylabel = "x", labels = reshape(["$k-step-preds" for k in steps], 1, :))This clearly illustrates how the quality of the prediction changes as we try to predict further into the future. While the 4-step-ahead predictions still look good, anything beyond that is almost useless.

Summary

There is quite a difference in difficulty between interpolation and extrapolation. Consequently, if you have a sequence, always respect the temporal order of the data when training, i.e., never train on future data. Given this kind of data, sequence models require specialized statistical tools for estimation. Two popular choices are autoregressive models and latent-variable autoregressive models. For causal models (e.g., time going forward), estimating the forward direction is typically a lot easier than the reverse direction. For an observed sequence up to time step

Exercises

Improve the model in the experiment of this section.

Incorporate more than the past four observations? How many do you really need?

How many past observations would you need if there was no noise? Hint: you can write

and as a differential equation. Can you incorporate older observations while keeping the total number of features constant? Does this improve accuracy? Why?

Change the neural network architecture and evaluate the performance. You may train the new model with more epochs. What do you observe?

An investor wants to find a good security to buy. They look at past returns to decide which one is likely to do well. What could possibly go wrong with this strategy?

Does causality also apply to text? To which extent?

Give an example for when a latent autoregressive model might be needed to capture the dynamic of the data.